RECENT WRITINGS ...BACK TO WRITINGS MENU

|

THE FINAL THREATS * * * PART ONE

INTRODUCTION

It was a long time coming, this very terrible break between AIDS officials in the government of Oaxaca and the members of our organization, the Frente Común Contra el SIDA (Common Front Against AIDS). Thirteen years, in fact. During that time the relation had been on-going, if sometimes rocky. Then our organization brought to their attention the lack of medications for AIDS patients in our state. The director of the state AIDS council, COESIDA, reacted first by ignoring our comments. When we continued, she then began moves to discredit our organization and later to hinder our work. The naming of Oaxaca as host for the national AIDS convention last year brought the matter to a head. There could be no criticism of government officials in Oaxaca. This corresponded with the now well-known public movement against the government and the brutal wave of arrests, disappearances and political assassinations which followed. Thirty-four opposition leaders were killed in 2006 alone.

It was a long story, as I say, and complex. It begins with the founding of the state council on AIDS, COESIDA, in Oaxaca. The following are excerpts from my journals during those years.

THE FOUNDING OF COESIDA, OAXACA

The year was 1993, and our organization, the Frente Común (Common Front Against AIDS) was only a year old but we had been busy and felt good about our work. Our little Information Center was open on Morelos Street, right in the heart of the city, and lots of people were stopping by. Our press campaigns had been successful and our talks in the schools were well under way. Further, our work had been noted by high health officials in Mexico City.

One day Nancy Mayagoitia, our founder and “voice” of the Frente, was talking to Alberto Treviño on the phone. He was the head of CONASIDA, the national AIDS council in Mexico City, and he says, Nancy, we have an idea we think you can help us with. Seems that CONASIDA (Consejo Nacional) had been founded in 1986, around the same year as the new laws about blood testing and other things, and at the same time they had “mandated” that each state shall have a state counsel; they would be called COESIDAs (Consejo Estatal). Well, in most states they were moribund, nobody had done anything and didn’t have a clue what to do. Oaxaca included. So, he says, they’re thinking of “restructuring” the COESIDAs, and how would you, Nancy, and the Frente, of course, like to help us out and do a major “restructuring” of the Oaxaca COESIDA, and it would be, like, a pilot project for the other states. Nancy said, Well, we’ll think about it. Now remember that Nancy's husband, Alfonso Sandoval, was a rising star in the PRI, the party in power for over seventy years, and Nancy was his hard-working wife, helping along the career of her husband, and the governor, who was also PRI, of course, was all schmoozy with them and the Secretary of Health, also PRI of course, was a Doctora María de las Nieves García, and everybody wanted to be a big-shot and to do a national “pilot project” for the Federal government was a wonderful idea. So, Nancy and I got a meeting with Dr. Nieves and went to her office. It was just the three of us. Nieves, I noticed, was all gushy with Nancy, I guess thinking about how important Alfonso was and all. Oh, yes, she wanted to help however she could, she said. I could tell, however, she didn’t have a clue about AIDS or any apparent interest in the subject. I would learn later that this is typical of all the Secretaries of Health appointed in our state. It is a political office, held by politicians going up the ladder, and abandoned at their first opportunity of a better position. But at the time I was trying to impress her and get her interested in having our own COESIDA here in Oaxaca. I had been playing around with a Oaxaca-looking letter style in my head for a while and suddenly I saw how I could write out a simple logo for COESIDA. I smoothly took a piece of note paper from my things and doodled out the simple letters as they came to me. Across the bottom I drew a little zig-zag design like you see in Mitla, the famous ruins down the valley. “And, see,” I spoke up, pushing the paper across her desk at her, “we could have our very own logo, something like this, real Oaxaca-ish, you know?” “Oh,” she sat up, “that’s beautiful! Yes, I like that. We could have that for our logo!” Nancy looked at the sketch and then gave me a big smile. “One of the advantages of having an artist on staff, Doctor,” she remarked sweetly.

It was decided. Yes, there would be a “new” COESIDA in Oaxaca. It would be called COESIDA, Oaxaca. And we would be in charge of setting it up and writing the rules and getting it started. The Frente Común, of course, would continue working, like always, but four of us would “go over” to the state Secretary of Health for six months and help establish the first active COESIDA in the country. It was a long six months. It would be Nancy, as “executive director,” Dr. Bertha Muñoz as “technical director,” and Paco Espinoza, our cute, little gay male-nurse, and myself. I forget Paco and my titles.

We had a lot of meetings at Nancy’s house, writing the rules and regulations of the new COESIDA, and how we thought it should be. I wasn’t much of a help, really, mostly pacing and listening over my shoulder, as Nancy and Bertha pecked it out on the computer. Occasionally Nancy would ask me a question or what was my opinion about something. And we worked hard. All services should be free, we said. And confidential, patients would have a numerical code, for all paperwork. We would offer the HIV test, free to all. A psychiatrist would see each person, before and after having the test, to make sure they understood what it meant. A doctor would see each HIV positive result, and set up monthly follow-up appointments. The latest medicines, at that time mostly AZT, would be given out to all who needed them, again cost free. It was good work and we felt proud. Our Oaxaca branch of COESIDA was set to open. But where?

I had always liked Dr. Bertha Elena Muñoz a lot and we had worked well together. When the Frente first started, she was head of epidemiology at the big general hospital in Oaxaca and, as such, in charge of all AIDS patients in the state. She knew a lot about AIDS and was a tireless worker. I had a tremendous respect for her. One day I got a call. “Bill, you want to come look at a space with me, don’t you!” It wasn’t a question. I said, sure! She picked me up and we went to a nearby address on Independencia Street, close to the center of town, a big old building around a central patio with about eight rooms of different sizes. “Let’s take it,” I said. She said she had to negotiate with the landlady.

Well, it dragged on for a couple months, and then it dragged on for a while longer, but in the end we rented the space.

* * *

Then it was around the first of the year, 1994, and we had the space and I’d been in it a couple times, but it seemed nothing was really getting going. I went to see Nancy and said, "Nancy, I want to take Doctor Nieves into the building myself and show her around and get her enthused and such, you know?" Nancy thought about it for a minute and said, "Bill, I have to go into the gallery today, but I’ll see what I can do.” That night, there was a message from Nancy that she has a meeting for me with Nieves at 10:30 in the morning. I called her up and thanked her and we said we’ll see you in the morning.

Below: Secretary of Health Dr. María de las Nieves.

The next morning, Bertha, Nancy, and I were at Nieves' office and 10:30. There we sat in the patio enjoying the flowers. The workers in the office said the Doctora would be here soon. We waited for nearly two hours. Well, I could have told you she would never show after about 30 minutes, so finally we walked over to the new COESIDA offices anyway and ended up having a good meeting among ourselves. We decided to get the ball rolling and open the clinic ourselves. We planned an inauguration.

* * *

It was a nice inauguration. Dr. Treviño, from the National council, came. I wrote two of the speeches, one for Nieves and one for a Doctora Gabriela Velásquez, whom Bertha had contracted as assistant director. I decorated the place up real nice. For some reason, our friend Dr. Méndez Sumano was there and it was decided he should sit up at the main table with all the functionaries but he was not wearing a nice coat or anything and he was running around looking nervous. Then he saw me and my nice jacket. He motioned me to come over and join him in the corridor where he convinced me to loan him my nice (over-sized) jacket I was wearing. I told him he owed me big.

It was a long six months, I tell you. More than anything, it wasn’t our style. State workers can fill hours and hours and days and days of doing nothing at their desks. Make-work, I guess you call it. And the only important thing is to always be at your desk. Well, I had lots of things to do, and running around and being away from the offices, and they didn’t like that. They would prefer I was in the office doing nothing, with them of course, than out seeing to the printing, making contacts, setting up workshops, picking up fliers, and a million other useful things I had to do. It was driving Paco crazy too, and soon the Dra. Bertha says, that’s it, let’s go, and we left the place in the hands of Dr. Gabriela Velásquez.

Below: Dr. Gabriela Velásquez (left) with Dr. Alberto Treviño of CONASIDA. Dr. Velásquez is the wife of the largest contributor to the political campaigns of both ex-governor José Murat and current governor Ulises Ruiz. She would later win the Loungines Swiss Watches' "Elegance and Attitude" award.

In the end we had worked hard and felt good about our efforts. Patients were being seen and given medicine (at that time only AZT). The HIV test was available to anyone who asked. Psychological attention was provided to all clients. A strict system of confidenciality was established. Best of all, all the services of the clinic were absolutely free. Our COESIDA, Oaxaca, would become known as one of the best AIDS clinics in the country. And we, the four of us, Nancy, Bertha, Paco and I, could go back to our great little Non-Governmental Organization, our "common front," and get to work in the style to which we were accustomded.

* * *

OUR FIRST BIG COLLABORATION WITH COESIDA: “OAXACA RESPONDS”

So, a couple years later, kicking around Oaxaca and very busy, of course, but always open to a new project or at least a reason to do a big show, somebody heard that COESIDA was planning a big, important “training workshop” or such, for doctors in the state, and that it was going to be presented by some doctors from UCLA, the big AIDS department there. And everybody was saying it was going to be a big deal. It sounded wonderful. The idea was to bring the latest medical information to Oaxaca and get it to doctors and health workers throughout the state. They said about 250 would attend. The workshop would last a week. We thought it was just the kind of thing COESIDA should be doing. How could we show our support and help out COESIDA doing their workshop, we asked our selves. Well, it sounded like lots of doctors and such from around the state, would be here in Oaxaca for a full week, with nothing to do in their evenings, for five days and five nights. Hey! So, we did up a little plan and went to see Dra.Gaby and give her our proposal. We said how we thought their workshop was a really good thing and that we wanted to help and how about if we presented a series of, well, AIDS-related cultural events during the week, in the evenings after the sessions? And it would be a joint project, with COESIDA doing, of course, all the medical stuff, and the Frente Común doing all the artistic stuff, natch. Well, the Dra. Gaby said she thought it was a wonderful idea and said, sure, Bill, let’s do it. I asked her what else she thought we could to help her and she said, well, it would be nice to print a good-looking booklet of the course and the agenda for the week and such. I said, Hey, no problem, we’ll get right on it. I went to see my friends Claudio and Martha Sánchez with the printing shop, who had done lots of nice contributions for us and were always extremely helpful, and they said, wonderful, Bill, we’ll do a nice job and contribute the printing, you guys cover the materials only. That was very nice of them. So, we got started and the little booklet was looking great. I had, several years earlier, designed the COESIDA logo, if you remember, and have always enjoyed reusing it and playing with that style of lettering and such. We did a nice cover and convinced Dra. Gaby to call the conference “Oaxaca Responds” and to play up the support of the people, and certainly the artistic community, to this fine effort. As a little design feature for the book, I used the simple symbol of the red ribbon, first on the cover in red, and then, in pale grays behind the text, the same symbol becoming more abstracted throughout the book. It was nice. They gave us the agenda and some good information about the course and subjects and then too, we slotted in our cultural events. There would be one each night, Monday through Thursday, and we would “stage” the closing ceremony on Friday afternoon. That would be it, plus the nice course handbook we were designing. They liked it all and we were “go.” One of the other ideas we had, was to invite a few important people to contribute a few words of introduction to the handbook, and we would include them in the first part right after the nice “contents” page at the front. We asked Dra. Gaby to write something for it, of course, and one of the professors from UCLA, a nice guy we would get to know well, and then thought it would be good to include something from Nancy, as head of the Frente Común. Well, they all responded well, and we got their texts and slotted them in, a couple pages from Dra. Gaby, a nice long piece from Nancy, and a brief overview from the professor, and ran them one right after the other for the first six or seven pages of the booklet. I ran it over to Claudio and Martha in good time and they said sure, Bill, we’ll have it for you in a day or two.

On all fronts the project was looking great. For the Monday night, we had spoken to the MACO, the Contemporary Art museum, as well as the major galleries in town and arranged an “opening reception” in the museum courtyard, followed by a “walking tour” of the galleries, where each of the galleries had a nice little spread and refreshments. Those days our friend, the crazy “artist.” Reto Morger (BELOW), had been working on a kind of “performance happening” featuring an AIDS theme, of a dying patient writing AIDS obscenities with his own blood on the inner surface of his oxygen tent. We would hand out signed-bloody syringes to passers-by. That sort of thing. It was scheduled in front of the Cathedral on Tuesday evening.

For the Wednesday, we slotted in Dino Castro’s great AIDS one-act, “Interpret My Silence” (BELOW) into the nice Sala Juárez of the University’s Fine Arts Department, where we had done it the year before on World AIDS Day.

And then for Thursday night, the final night before the close of the conference, we requested and received a donation of the big, Beaus Arts theater, the Macedonia Alcalá, to bring to Oaxaca city our fabulous Juchitán drag show, “Las Intrépidas VS. SIDA.” We heavily publicized a FREE DRAG SHOW!!! For the closing ceremonies, after such a (whew!!!), culturally filled week, we decided to spruce up the short ceremony by opening with a couple pieces by a classical string quartet from the school of Bellas Artes. We knew this nice group of kids, who were eager to perform and sounding great. They wanted to donate their performance, but we insisted on a token $200 pesos, to cover their taxis and make them feel kind of good about actually having a “gig.” Each event, of course, had its own posters and programs and it was a lot of work. And then with the scenery and extra materials here and there, it was costing a bit of a bundle. But we liked it a lot and we were getting a lot of attention.

* * *

So, the opening day came and everything was in place. Claudio and Martha had sent the booklets over to COESIDA, and they were all ready, I had heard, and we showed up early for the opening session. Nancy had been invited. The event was taking place in a big rented hall in the Hotel Misión de los Ángeles, on its big, leafy grounds, and it all looked pretty. A few of the COESIDA people were gathered at the doors and handing out the nice little booklets to people coming in. I took one in my hand and looked at it proudly. “Oaxaca Responds” it said with a nice little red ribbon printed on the cover. Then I noticed it felt a little light in my hand, a little flimsy, thinner than I expected. Also, it was kind of loose, and falling apart, like it wasn’t quite stapled correctly. Not at all like Claudio and Martha’s usual fine work. I opened the book. The first page was the “Contents,” a little red ribbon in the corner. I turned the page. I knew the booklet well. It jumped right to the center page of the book, the agenda! All the introductions and first pieces about the cultural events, were all missing! And then after the center page of the agenda, it jumped right to the final page of references and acknowledgements. And that was it. Over two.-thirds of the little booklet was missing. It had been torn out! And the remaining few pages hung there limp on the staples and sliding around. I grabbed another one from the stack by the door. The same. And another, the same. All the booklets were missing two-thirds of their pages. “What happened to the handbooks?” I demanded of one of the little COESIDA workers. She looked down sheepishly. She didn’t know anything about it. The others were looking away nervously. I finally found somebody who would talk to me. It was the Doctora Magda. “It was decided. I’m sorry.” “What was decided?” I insisted. “It was decided that it was totally inappropriate to have Nancy Mayagoitia’s comments in the book. She’s with the Frente Común. The Frente Común has nothing to do with this. I’m sorry,” and she walked away. Now I got it. They had decided to remove Nancy’s name and words from the book, in some sort of silly spite, I guess, and, hence, had to pull out Gaby’s introduction too, it being printed on adjoining pages, and you couldn’t have Gaby’s comments end funnily in mid-sentence. And so they had to remove the UCLA professor’s for the same reason, and their adjoining pages about the cultural events planned by the Frente. All ripped out. Further, the book being a “saddle” staple form, all the facing pages of all those pages, of general AIDS information and statistics and the outlines of the courses and lots of good stuff like that, all had to come out too. So that was it. Our nice little booklet, with lots of good information and plenty work, let me tell you, was reduced to a silly little pamphlet, hardly holding together. In addition, my simple use of the AIDS ribbon and its repeated abstract forms, meant nothing at all, a few odd shapes, looking like ridiculous errors, appeared on a few of the pages but made no sense at all. I shook my head. Well, get over it, Bill, I told myself. That’s bureaucracy for you. Besides, nobody would speak to me about it or acknowledge they even knew. Except Nancy, of course. “What happened to the book, Bill?” she asked. I explained. And she agreed with me. “Get over it, Bill. That’s the way they do things.” Well, the rest of the week went great. Almost. On Monday, all the galleries had put up nice displays of support for the course, handed out little red ribbons throughout the week. On Tuesday, Reto’s bloody profanities in front of the Cathedral stopped traffic. We filled the Sala Juárez for Dino’s piece on Wednesday and then filled the big old opera house “to the rafters” for the big FREE DRAG SHOW on Thursday. They told us there were people sitting in upper reaches of the theater where people hadn’t sat in years. The Intrépidas knocked ‘em dead, of course. Our theater director, Sergio Santamaría, made a nice speech at the end (BELOW), thanking all the people who had come to ur shows during the week, for helping to show that "Oaxaca Responds."

We were feeling particularly good, then, on Friday, when we went early to oversee the nice closing ceremonies we had planned at the hotel. I poked my head in the door. I was told by the little, shy COESIDA worker in the lobby that they were running a little late, and the next-to-last session in the room, was still going on. Fine, I said, and strolled out onto the lawn. I was looking around for the little string quartet we had arranged and who had said they’d be there early to have plenty of time. They weren’t anywhere to be seen. So I walked around a little bit and then looked back into the lobby. The little shy girls at the door were staring at the floor. I went over. “You haven’t seen the string quartet, have you? You know, the musicians who are coming?” They hemmed and hawed. No, they shook their heads. They didn’t know anything about that. I suddenly got a small prick of suspicion up my back. I went looking for somebody else. I found Dra. Magda. “What? That band?” she screamed at me. “I sent them away, of course!” and she turned to go. “You what?” I couldn’t believe it! “They wanted to play music! Imagine! I told them we had no need of any music here! They left.” She said “music” like it was the most disgusting maggot on earth, to be squashed underfoot. She stomped off, indignant. I later heard she was particularly incensed that they thought they would be paid. “Paid! Forget it! Out! Get out at once!” she had screamed. So that’s why the COESIDA workers were all wearing smug little smiles on their faces; they had saved poor COESIDA from PAYING for some stupid music! Well, get over it, Bill.

We did, of course, get over it. I scurried over to find the little string quartet we’d contracted and apologized profusely, and insisted on paying them. They said, No, they would only take half, for the taxis. And the week was long remembered as a wonderful success, the visiting people from UCLA thought we were great and said they hadn’t seen such community support in ages. We became friends and would know them later in Los Angeles. And we would know a little better the simple rules about what to expect from our friends at COESIDA. Mainly, nothing. Anything we did all ourselves, we could do fine. Anything which involved them, they would somehow totally screw up. The little booklet, a disaster. The nice closing ceremonies, canceled.

There would be future collaborations with COESIDA, some nice, some not so nice, but those simple rules, we found, would always apply.

* * *

OUR SECOND COLLABORATION WITH COESIDA: “NIGHT OF THE CANDLES”

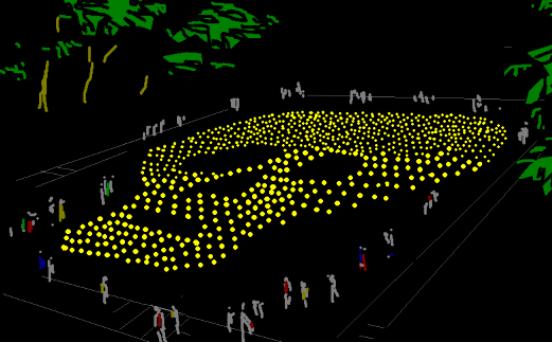

So a couple years later, it was the fall of 2000, we’re hanging around and enjoying our big new Center above the rushing Periférico of Oaxaca, and busy, but, also, kind of looking around for another project, when I happened to hear that our friends at COESIDA were planning a candle-light march in honor of AIDS deaths for the big Day of the Dead festivities on the first two days of November. I guess they had done it before, which I vaguely remembered, and they were going to repeat it this year. I had always felt that the use of death as part of our message was particularly delicate. We had even some time before, decided to take the big death symbol out of our talks in the part about the stages of the illness; with the new medicines and a certain sense of hope in the advances against AIDS, we felt it was a little heavy to always say the last stage is death. So we had never really done anything, as a group, connected with the big Mexican holiday, Day of the Dead. And, of course, remembering our many previous collaborations with COESIDA, we knew a little to expect a few bureaucratic hassles from them, and be prepared to do pretty much anything ourselves, if we wanted to get it done. But, as I say we were looking around for a project. So Ayax and I went over to see Dra. Gaby and see what she had to say. Well, she was happy (I guess) to see us and we chatted and yes, they were going to do a candle-light march, the night before the first of November, and it would be very nice and a solemn affair and end up in the Alameda de León in front of the Cathedral. We suggested to her that we take charge of the part in the Alameda and that we do an installation of candles, of the number of AIDS deaths to date, in a big design of light in the shape of a skull, and that their candle-light walk would end up at our installation, and we would consider it a “joint project.”. We had drawn up on the computer a beautiful overhead view of what it would look like.

Well, she liked the idea a lot and said at once, oh, yes, let’s do, Bill. It’s a beautiful idea. And we shook hands on it. “You’ll tell your people that we’re doing it then?” I asked, remembering past resistance from some of her lower administrators. I wanted the boss’ word. “Oh, yes, Bill. Don’t worry.” She said she would get us the latest figures on the number of AIDS deaths so far in Oaxaca as an estimate and then update the number right up to the event, if possible. I said fine. She said it could be around five hundred. That’s a lot of candles.

Those days, too, Pina Hamilton was hanging around and stopping in occasionally to say hello and see how we were doing. She thought the candles event was wonderful.

“I can get you the candles, Bill,” she said. “You can?” “Yes, of course, the biggest candle maker in Oaxaca is my cousin, bla-bla-bla Fulano, of Candles de Oaxaca, of course.” Of course. So, we drove out to see Fulano cousin of the candles and he said, For you, Pina, anything! Of course, I donate the candles! I thanked him profusely and suggested that we would like to get a nice picture of him for the papers and all, having donated the candles and such. No, no! I don’t want to have anything in the papers and no names please. Pina leaned to me, “Bill, you got the candles. Let’s go.”

So it turned into a big project, of course, and we decided that we had to take the original paper wrapping off the candles, which was real ugly, and put our own, nice, hand-cut white sleeves on each of the candles. A lot of work. And we decided that the candles should also each sit on a little, round cut-paper base. They were beautiful.

Then we made twenty-five little black, one-foot high stanchions, cut and painted, a big silver screw-eye in the top each holding a new, thick, white nylon rope. It would outline the peripheral of the skull. It was all looking very good. We were planning for some music to be played and were listening to some Phillip Glass that we liked a lot. We had talked to our sound rental guys and everything was go. We took photos of the staff and the candles and prepared several nice press releases to go out shortly before the event.

And we were occasionally checking in with COESIDA because, well we had to, and then the first few little complications arose. It seems the location had to be changed. It was to be moved from the Alameda, in front of the Cathedral, to the Atria, on the side of the Cathedral, a much less desirable location for our event. Now, here too, it starts to get a little ridiculous. You see, the Alameda is actually City property, and COESIDA is a State institution, and the City is the PAN party and the State is PRI party and the two can never talk with each other We sighed. “Well, hell,” I said, “We’re good friends with the City. I’ll get us permission.” “Oh, no, you can’t do that.” I convinced them I could and I went in the following day and the guys at City Hall, our friends and long-time supporters said, sure, Bill, that’s a great idea. No problem. I reported back to a meeting of some of the COESIDA people that yes, we had permission to do it in the Alameda and no problem. I could tell that some of the group of female administrators that Dra. Gaby surrounds herself with were major miffed, but I thought Oh, well, let’s just do it. We still had Dra. Gaby’s authorization on the project.

Then, generally reporting on our work I happened to mention that our press releases were looking good and showed then some photos of the candles and how they were looking. “You mean, you’re... you’re...going to have ‘publicity’?” someone said as though it were the nastiest word in history. “Well, of course. We want as much publicity as we can get!” I said. “All the papers, all the media!” “Why, that ...that just ... CHEAPENS the event!” said one of Gaby's administrators. “Yes,” said another, “that doesn’t show proper respect for the dead.” “It’s just making it into a CARNIVAL!” Gaby was looking about to cry as usual and I was rolling my eyes thinking let’s get the hell out of here. “Listen,” I said, “you’ll all like the press releases a lot, I promise, and anyway we’ll be having another meeting again soon and we can talk about it more. OK?” So we got out of that meeting and I said to the guys, Get those damn press releases out to the papers at once! We did. They came out the next day and looked great and a lot of people were getting very interested. Nancy said, “I was a little surprised you’re doing that project. Bill, at Day of the Dead, you know. But it sure looks nice. Congrats!” We had been billing it as a joint COESIDA and Frente Común project, even though they were doing nothing. I had heard nothing about their candle-light march and kind of assumed it wasn’t happening. I would be proved right. There had been no plans for a candle-light march and it later fizzled. Oh, well. Then the statistics we were getting from Dra. Gaby went quickly over eight hundred. So, we got nine hundred candles and cut the sleeves and bases. We got the group, Conciencia Juvenil, from the Casa de la Mujer, a bunch of kids we liked a lot, to help out and be the candle-lighting team. A dress rehearsal was planned and a special black T-shirt for the candle-lighters was printed with the gleaming points of candle-light in the shape of a skull. It all looked great. The date neared.

At the next meeting with the administrators of COESIDA, Dra. Gaby not being available, I told them that the press releases had already gone out and in fact they could see the results; I showed them the coverage. There was nothing they could do about it. They were furious. I tried to change the subject and somehow mentioned the sound system for the music. “Music!” they screamed. “You’re going to have MUSIC?” They were livid. “We’ll see about that!” said Ofelia, and she stormed out.

The day before the event I met once more with the staff of COESIDA. Ofelia met me at the door. She began, “It’s canceled!” “What? What’s canceled?” I stuttered. “The whole event! It’s OFF! There was a meeting, and no one liked anything about the way you are doing the event and it was decided better to not do anything at all, and so it’s canceled.” “But, ...but what about Dra. Gaby, what does she say?” “Doctora Gabriela does not want to talk to you. I’m sorry. Goodbye.” I was standing in the entrance of COESIDA, shocked, of course, and shaking my head. The dress rehearsal was that day. The kids were coming over shortly with their new T-shirts to practice lighting the candles. With the music. I looked at the Licenciada Ofelia. “Well, I got to tell you something, Licenciada:” “What?” “It’s going to happen.” “No, it’s NOT.” This was going nowhere. “Listen, tell the Dra. Gaby to stop by tomorrow night and see for herself how nice it is. Adiós, Licenciada,” and walked out.

* * *

Well, it was a stunning event and a lot of people saw it and it got on the front pages of all the papers the next day. In the end, we had our president, Lilia Palacios, call up Dra. Gaby at her house and say something like Oh, and I do hope you’ll come by tonight, Gaby, I’m so looking forward to seeing you.

About six o’clock we set up the candles, it was still light. It took awhile, there were a lot, exactly 845. We had made nice little fliers to hand out with a picture of a single candle, in our hand-cut sleeve and base, and the big number 845. Then about seven we started the music; a series of haunting pieces from Phillip Glass’ “Glassworks” album, filled the streets. The kids, dressed in black and holding a long white taper began moving down the large pattern of the gaping skull.

People began slowly gathering and walking around the large skull. The kids kept the candles burning long into the night, the tense, dramatic notes of Phillip Glass’ organ sounded, and thousands passed silently by our glowing installation. Dra Gaby did come, finally, and Lilia escorted her around the long white rope with its little black stands, pointing out our little sign which still said a joint project with COESIDA. “Isn’t it beautiful?” said Lilia. Gaby just scowled and left.

* * *

|